Oliver Page

Case study

August 29, 2025

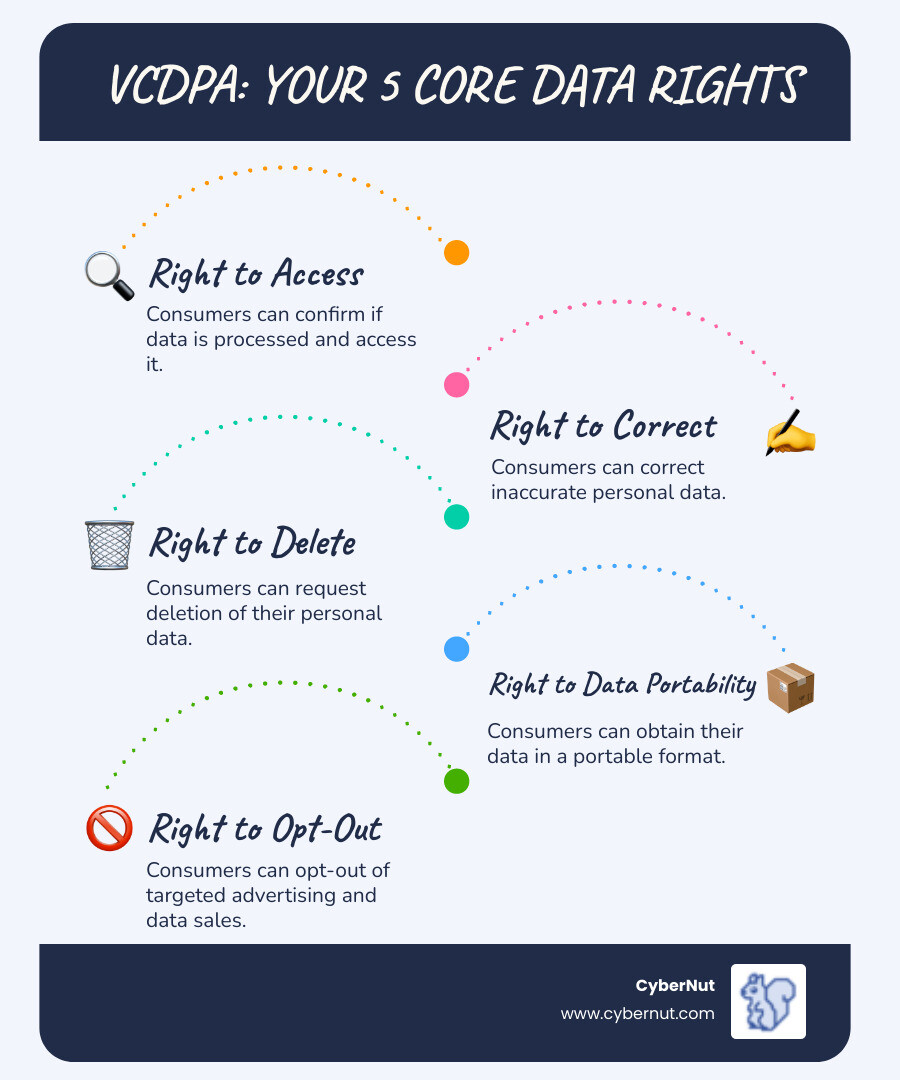

All About the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act for K–12 Districts involves understanding how this comprehensive privacy law creates new obligations for handling student, parent, and staff data. The VCDPA, effective January 1, 2023, grants Virginia residents five key consumer rights and places specific responsibilities on organizations that process personal data.

Key VCDPA requirements for K-12 districts:

Although many Virginia school districts qualify for exemptions as government entities, the law still impacts how they work with vendors and respond to privacy requests. The VCDPA adds to a complex privacy landscape including FERPA and COPPA, requiring IT directors to update data governance, review vendor contracts, and ensure staff understand the new rules.

Understanding these obligations helps districts build stronger data protection practices, maintain trust with families, and avoid potential penalties of up to $7,500 per violation.

The Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act is a comprehensive privacy law that gives residents control over their personal information. It establishes clear consumer rights for individuals, data controller obligations for organizations that decide how data is used, and data processor duties for companies that handle data on behalf of others. The Virginia Attorney General handles enforcement. For legal details, see the official text of the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act.

Understanding the law's key terms is crucial for school districts.

A consumer is a Virginia resident acting in a personal capacity. For schools, this typically means students and parents, but not staff in their employment context.

Personal data is any information that can be reasonably linked to a specific person. In schools, this includes student names, grades, IP addresses, and behavioral data from learning platforms.

Sensitive data receives special protection and includes health information, racial background, and any personal data collected from a known child. This means most student information in K-12 districts could fall into this category.

The controller is the entity that decides what data to collect and why. The school district itself is usually the controller.

A processor handles data on behalf of a controller. EdTech vendors, cloud storage providers, and student information systems are typically processors.

The sale of personal data means exchanging information for money or other valuable consideration. Schools must be careful with data-sharing arrangements to avoid this classification.

The VCDPA has an important state agency exemption. The law generally does not apply to any "body, authority, board, bureau, commission, district, or agency of the Commonwealth" or its political subdivisions.

As political subdivisions, school districts often qualify for this local government bodies exemption for their core functions. However, the VCDPA is not irrelevant to schools.

Even if districts are exempt, they work with many third-party vendors who are subject to the law. When schools share data with EdTech companies, those relationships must comply with VCDPA requirements for processors. Furthermore, while employee data is often exempt, student and parent data can still fall under the law's protection, especially when shared with commercial vendors.

The bottom line is that understanding the VCDPA helps districts ensure vendor compliance, handle privacy requests properly, and maintain strong data protection practices.

Understanding the VCDPA means knowing the rights it grants to individuals and the responsibilities it places on school districts. These rights and obligations form the core of the law's data protection framework.

The VCDPA gives Virginia residents five key rights over their personal data, which primarily apply to students and their families in a school context.

The right to access lets consumers confirm if you are processing their data and get a copy of it. A parent could ask to review all information a district has collected about their child.

The right to correct allows consumers to fix inaccurate personal data, such as an incorrect phone number or an error in a health record.

The right to delete allows consumers to request the removal of their personal data. This is limited in schools, as some records must be kept for legal or educational reasons.

The right to data portability lets consumers obtain their data in a format that is easy to transfer to another service.

The right to opt-out covers targeted advertising, the sale of personal data, and profiling for automated decisions. This is especially relevant when districts use EdTech that might engage in these practices.

The VCDPA gives special attention to rights for known children. Data from children under 13 is automatically considered sensitive, typically requiring parental consent before processing.

Even with exemptions, following these VCDPA principles helps districts build trust and strengthen data protection.

Data minimization means only collecting data that is truly necessary for a specific purpose.

Purpose limitation requires using data only for the reasons it was originally collected.

Data security duties mandate establishing reasonable administrative, technical, and physical safeguards to protect personal information.

Consent for sensitive data means getting clear permission before processing sensitive information like health data or most data from young children.

Non-discrimination prohibits penalizing consumers for exercising their privacy rights.

Data Protection Assessments (DPAs) help identify and reduce privacy risks. While not always required for internal processes, they are a smart practice, especially when working with vendors or engaging in high-risk activities. DPAs are necessary for activities like targeted advertising, the sale of personal data, and processing sensitive data, which is common in K-12 settings. The assessment weighs the benefits of processing against privacy risks and identifies ways to mitigate them.

The VCDPA joins a family of federal and state regulations that shape how schools handle personal information. Understanding All About the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act for K–12 Districts requires seeing how it fits with laws like FERPA and COPPA. These laws generally work together, but districts must know when each applies.

The VCDPA explicitly states it does not apply to "personal data subject to the federal Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act." This means FERPA takes precedence for educational records like grades, attendance, and disciplinary files.

However, the VCDPA can still apply to data not subject to FERPA. This might include website analytics, information from non-educational parent surveys, or data from apps not tied to educational purposes.

The VCDPA's COPPA alignment is also key. It treats data from children under 13 as sensitive, requiring parental consent, which mirrors COPPA's requirements for collecting information from young children online. While Virginia lacks a specific Student Online Personal Information Protection Act (SOPIPA), the VCDPA's rules on data sales and targeted advertising offer similar protections for EdTech use.

The VCDPA's biggest impact on schools is through vendor management. Your EdTech providers and other vendors are almost certainly subject to the VCDPA and act as data processors when you share data with them.

This means your controller-processor contracts need specific language about how vendors handle personal data. Key requirements for these Data processing agreements (DPAs) include:

The VCDPA has key differences from other state privacy laws.

For K-12 districts, VCDPA compliance is about creating a culture of data protection. Even with governmental exemptions, treating VCDPA requirements as a baseline for best practices is the smartest approach, especially when working with vendors.

A clear compliance roadmap makes the process manageable.

The Virginia Attorney General (AG) exclusively handles VCDPA enforcement, meaning no private lawsuits from individuals.

Until January 1, 2025, the law includes a 30-day cure period. If the AG finds a violation, your district has 30 days to correct it and provide written assurance that the issue is resolved. If fixed properly, no financial penalties are issued.

However, if violations are not corrected, civil penalties can reach up to $7,500 for each violation. While direct penalties for exempt school districts may be less likely, non-compliance can still damage your reputation and lead to scrutiny. The cure period disappears on January 1, 2025, making proactive compliance even more critical.

We know that even after diving deep into the VCDPA, some questions linger. Let's tackle a few common ones that often pop up for K-12 districts when discussing All About the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act for K–12 Districts.

Generally, no. The VCDPA's definition of a "consumer" excludes individuals acting "in the context of a commercial or employment relationship." This employee data exemption means that data collected for employment purposes like payroll, benefits, or performance reviews falls outside the VCDPA's consumer rights framework.

However, the exemption is context-specific. If a teacher uses the district's public website in a personal capacity (e.g., signing up for a community newsletter), that interaction could be covered. Similarly, B2B data, such as vendor contact information, is also generally exempt.

The VCDPA defines a "sale of personal data" as exchanging it for "monetary consideration or other valuable consideration." While schools do not sell data for cash, the "other valuable consideration" clause raises questions about partnerships where a vendor provides free or discounted services in exchange for data access.

Most common school district activities avoid this by structuring vendor agreements so the vendor acts as a "processor" providing a specific educational service. Your contracts should explicitly state that data is shared solely for educational purposes and not for the vendor's commercial gain. A strong Data Processing Agreement is crucial to clarify that no "sale" is occurring.

The answer depends on the student's age and the context.

For children under 13, the VCDPA aligns with COPPA, meaning parental rights are primary. Parents or legal guardians are considered the "consumers" who can exercise privacy rights on their child's behalf.

For older students, the line is less clear. The VCDPA does not specify an age when rights transfer to the student. While a 17-year-old might have the capacity to make some privacy decisions, parents often retain significant rights in the K-12 setting.

A practical approach is to develop clear policies and, when in doubt, involve parents. Most schools find it easiest to work with parents as the primary contact for privacy requests to ensure consistency and build trust.

The Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act provides a framework for honoring the trust families place in schools to protect their data. All About the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act for K–12 Districts ultimately comes down to building a culture of proactive data protection.

Proactive data protection means weaving privacy and security into daily operations. By understanding data flows, strengthening vendor contracts, and training staff, districts don't just follow the law—they build trust with their communities.

However, policies and safeguards are not enough without a strong cybersecurity culture. Your staff is the first line of defense against cyber threats. When they can spot a phishing email or a social engineering attempt, they become a key part of your security solution.

At CyberNut, we specialize in making this happen. We've replaced boring, time-consuming cybersecurity training with automated, gamified micro-trainings designed for busy educators. Our approach builds practical skills that stick, making your staff a resilient defense against cyberattacks.

Combining VCDPA compliance with effective cybersecurity training creates a powerful defense system for your entire school community.

Ready to see where your district stands? Get your free phishing audit to find out how vulnerable your team might be to email-based attacks. It's a small step that can make a huge difference.

Oliver Page

Some more Insigths

Back