Oliver Page

Case study

August 4, 2025

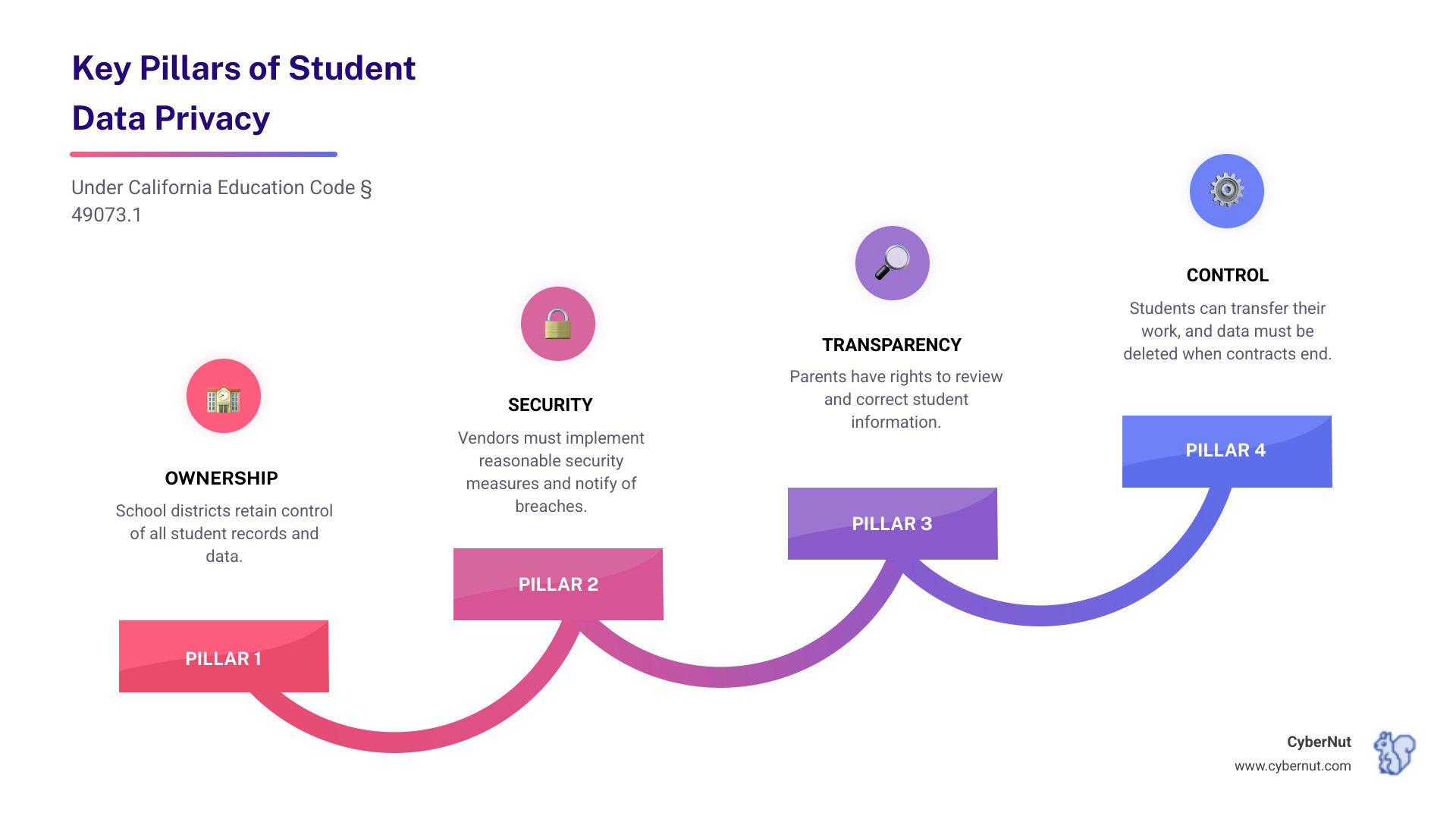

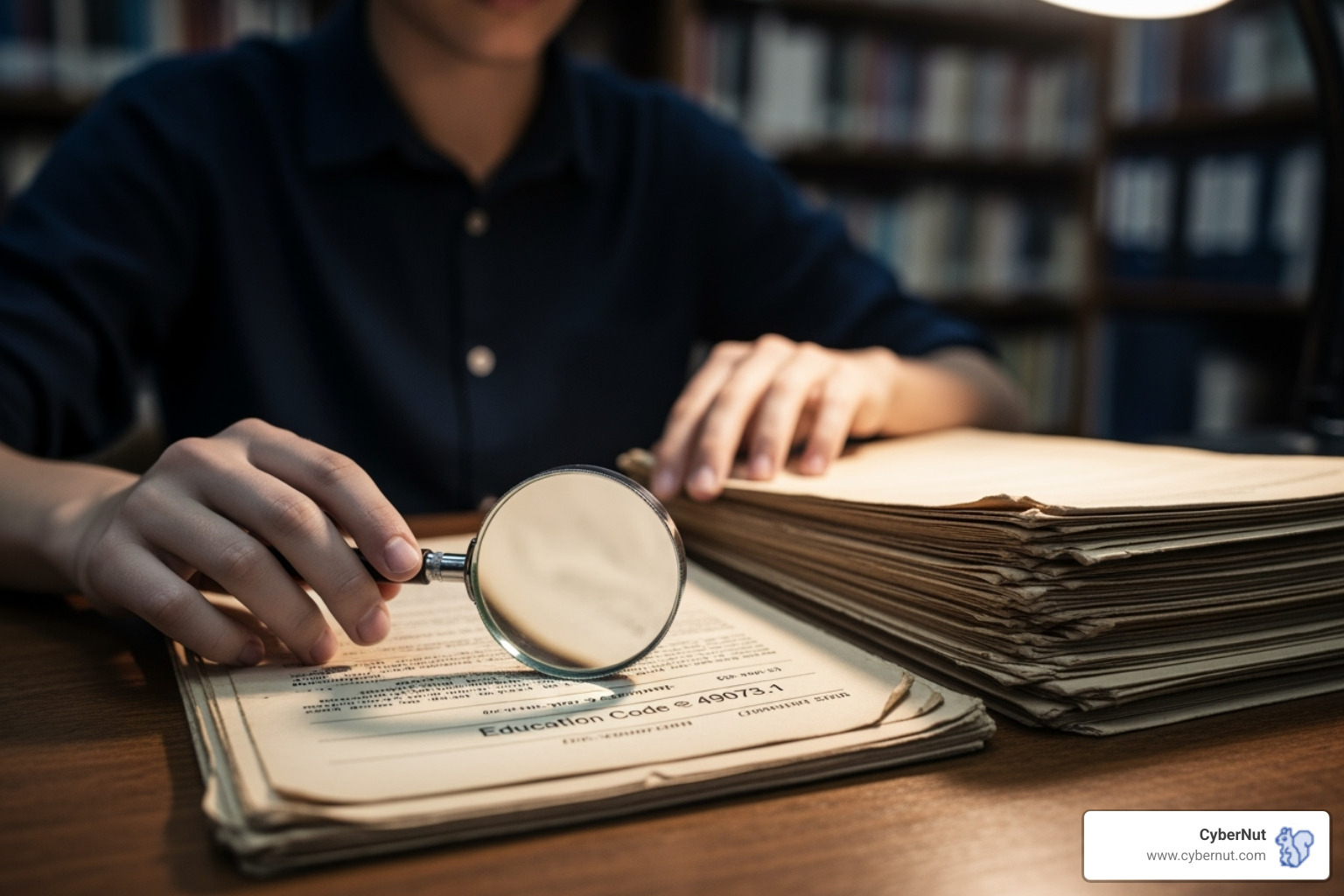

All About Education Code § 49073.1: How California Regulates Student Records Sharing starts with understanding that California was the first state to comprehensively address student privacy through legislation. As schools increasingly rely on digital tools and cloud-based services, protecting student information has become more complex than ever.

Quick Answer for K-12 IT Directors:

The law emerged from growing concerns about student data privacy in the digital age. Since 2014, nearly 400 student privacy bills have been introduced across 49 states, with California's legislation serving as a template for other states' policies.

Why this matters for your district: Without proper contractual protections, student data can be misused, sold, or inadequately protected. § 49073.1 gives schools the legal framework to demand strong privacy safeguards from their technology partners.

The human element remains critical - even with strong legal protections, staff training on data privacy and cybersecurity awareness helps ensure these protections work in practice.

Think of California Education Code § 49073.1 as a protective shield around your students' digital information. Originally known as Assembly Bill (AB) 1584, this law stepped in when schools started using more and more digital tools—and realized that student data was floating around in ways they couldn't control.

All About Education Code § 49073.1: How California Regulates Student Records Sharing comes down to one simple idea: when your school works with any EdTech company, you need a contract that spells out exactly how student data will be protected. This isn't just paperwork—it's your legal armor against data misuse.

The law applies to all California Local Educational Agencies (LEAs), which includes your public school districts, county offices of education, and charter schools. It covers any third-party contracts involving digital storage, management, or retrieval of student records, plus any educational software that touches student data. You can read the full text in AB 1584 (Third Party Contracts) —EC§ 49073.1.

Here's what sparked this law: schools were signing contracts with EdTech vendors without clear rules about student data protection. Student records were ending up in cloud storage services and digital educational software with murky terms about who controlled the information.

Education Code § 49073.1 changed that by requiring specific contractual language that prevents data misuse. Every contract must now include clear rules about data ownership, security measures, and what happens when the contract ends.

The law recognizes that digital tools are essential for modern education—but they shouldn't come at the cost of student privacy. It creates a framework where schools can confidently adopt new technologies while maintaining strict control over their students' information.

This is where the law gets crystal clear: your school district owns all student data, period. Even when an EdTech vendor stores or processes that information, they're just the custodian—never the owner.

Think of it like hiring a security company to guard your school building. They have access to the building, but they don't own it. Same principle applies to student data.

The law also protects pupil-generated content—anything students create while using educational technology. Students must have the right to control their own work and transfer it to personal accounts when they leave the service. This ensures that a student's digital portfolio or creative projects don't get trapped in a vendor's system.

Understanding the law's terminology helps you steer contracts more effectively. Pupil records include any information directly related to an identifiable student that your district maintains—grades, attendance, disciplinary records, and special education plans. The detailed definition is found in California Code, Education Code - EDC § 49061.

Personally Identifiable Information (PII) covers data that can identify individual students, either alone or combined with other information. This includes obvious things like names and addresses, but also unique student ID numbers and even certain biometric data.

Deidentified information is data stripped of all identifying details, making it impossible to reasonably identify specific students. This distinction matters because vendors can use deidentified data for legitimate purposes like improving their educational products.

Finally, a third party in this context means any company that contracts with your school to provide digital services involving student records. This covers everything from learning management systems to assessment platforms and communication tools.

These definitions create clear boundaries that protect student privacy while allowing schools to benefit from educational technology innovations.

When it comes to All About Education Code § 49073.1: How California Regulates Student Records Sharing, the real power lies in what it requires schools to include in their vendor contracts. Think of these requirements as a protective shield around student data - they're not just suggestions, but mandatory clauses that must appear in every agreement between schools and EdTech companies.

The beauty of this approach is that it puts the legal framework directly into the hands of school districts. Instead of hoping vendors will do the right thing, schools now have specific contract language they can point to when holding vendors accountable. At CyberNut, we see these contractual requirements as essential building blocks for any comprehensive Data Security and Privacy Plan.

The law draws clear lines in the sand about what vendors absolutely cannot do with student information. These prohibitions protect students from having their educational data turned into commercial gold mines.

No targeted advertising stands as one of the strongest protections. Vendors can't use personally identifiable information from student records to create targeted ads. This means your third-grader won't see ads for math tutoring services just because they struggled with multiplication tables in their learning app.

No unauthorized data use closes a major loophole that some companies might try to exploit. Vendors can only use student data for purposes explicitly spelled out in the contract - period. They can't suddenly decide to use attendance patterns for market research or repurpose assignment data for unrelated business ventures.

The prohibition on selling student data is exactly what it sounds like - student information cannot be sold, traded, or handed over to data brokers. This protection ensures that a student's academic journey doesn't become a commodity in the data marketplace.

Finally, vendors cannot build student profiles for non-educational purposes. While they can use deidentified data to improve their educational products, they're forbidden from creating detailed commercial profiles about individual students. This keeps the focus on learning, not on turning students into marketing targets.

Education Code § 49073.1 doesn't just restrict vendors - it actively empowers families by guaranteeing specific rights over student data.

Parents and eligible students have the right to review personally identifiable information contained in pupil records held by third-party vendors. Contracts must clearly explain how families can access this information, ensuring transparency about what data is being collected and stored.

When families find errors in their data, they have the right to correct inaccurate information. The contract must outline a clear process for requesting these corrections, giving families control over the accuracy of their educational records.

Students also maintain access to pupil-generated content - the creative work, projects, and assignments they create using EdTech tools. Most importantly, students can transfer this content to personal accounts, ensuring their academic work remains theirs even after the school's contract with a vendor ends.

The technical side of data protection gets serious attention under § 49073.1, with specific requirements that address both prevention and response.

Contracts must describe reasonable security procedures that vendors will use to protect student records. This includes training for staff who handle the data and implementing appropriate technical safeguards. While "reasonable" might sound vague, it typically means industry-standard practices like encryption, access controls, and regular security audits. For more details on secure data handling practices, check out our Data Processing page.

When things go wrong, vendors need a solid data breach notification plan. Contracts must spell out exactly how schools, parents, and students will be notified if student data gets compromised. Quick notification allows everyone to take protective action before more damage occurs.

Perhaps most importantly, contracts must address data deletion upon contract termination. When a school's relationship with a vendor ends, the vendor must certify that all student records have been deleted. The only exception? Students can choose to transfer their own created content to personal accounts with the vendor. This "clean slate" approach prevents student data from lingering indefinitely in corporate databases.

These contractual mandates work together to create a comprehensive framework that puts student privacy first. They transform vague promises of data protection into specific, enforceable obligations that schools can rely on.

Navigating student data privacy can feel like solving a complex puzzle where multiple laws overlap and intersect. Understanding All About Education Code § 49073.1: How California Regulates Student Records Sharing means seeing how it fits within a broader legal framework that includes federal regulations and other California privacy laws.

Think of it this way: federal laws set the foundation, while California's legislation builds additional layers of protection on top. This creates a comprehensive safety net for student data, though it can sometimes feel overwhelming for school administrators trying to ensure compliance. The Student Privacy Compass' Guide to State Student Privacy Laws provides helpful context for how California compares to other states' approaches.

Federal privacy laws like FERPA and COPPA establish nationwide baseline protections for student data. California's Education Code § 49073.1 doesn't replace these federal requirements—instead, it strengthens them by addressing gaps that emerged as schools increasingly relied on third-party technology vendors.

FERPA (Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act) has been the cornerstone of student privacy since 1974. It gives parents the right to access their child's education records, request corrections, and control who sees personally identifiable information. However, FERPA includes a "school official" exception that allows schools to share data with outside vendors without parental consent, as long as the vendor performs services the school would otherwise do itself.

This is where § 49073.1 steps in to operationalize FERPA's requirements. While FERPA sets the general rules, California's law specifies exactly what must be included in contracts with EdTech vendors. As the research notes, contracts must include "a description of how the local educational agency and the third party will jointly ensure compliance with the federal Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act." This joint responsibility ensures vendors become true partners in protecting student privacy, not just passive recipients of data.

COPPA (Children's Online Privacy Protection Act) focuses specifically on protecting children under 13 from online data collection. It requires parental consent before websites or online services can collect personal information from young children. However, COPPA only covers the youngest students and applies directly to website operators, not to the contractual relationships between schools and vendors.

California's § 49073.1 extends privacy protections to all K-12 students, regardless of age, by regulating what schools can agree to in their vendor contracts. This means even high school students benefit from contractual protections that go beyond what federal law requires.

California has created a comprehensive privacy ecosystem that includes several complementary laws. SOPIPA (Student Online Personal Information Protection Act) works hand-in-hand with § 49073.1 to create dual layers of protection.

SOPIPA directly regulates the operators of online services, prohibiting them from using student data for targeted advertising, selling student information, or building profiles for non-educational purposes. These prohibitions apply regardless of what a school's contract says—they're built into California law.

Meanwhile, § 49073.1 requires schools to include specific privacy protections in their contracts with vendors. This creates a complementary relationship: SOPIPA tells vendors what they can't do, while § 49073.1 requires contracts to spell out what they must do. Together, they ensure student data protection from multiple angles. You can learn more about SOPIPA in this detailed SOPIPA guide.

The state's broader privacy laws, including the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), also play a role in this ecosystem. However, these general privacy laws include exemptions for data governed by FERPA, which means student education records are primarily protected by the education-specific laws like § 49073.1 and SOPIPA.

This layered approach might seem complex, but it creates robust protection for student data. Schools benefit from having multiple legal tools to ensure their technology vendors handle student information responsibly, while vendors have clear guidelines about their obligations under California law.

While these laws provide a strong legal foundation, ensuring your district's practical defenses are just as robust is critical. At CyberNut, we help schools move from compliance to true security. To understand your district's vulnerability to one of the most common threats, consider getting a free phishing audit to test your staff's awareness and fortify your human firewall.

Oliver Page

Some more Insigths

Back